Some 120 years ago, a kitchen oversight sparked an internecine battle, spawned what today would be considered industrial espionage and changed the way the world starts its day.

Yet when what is today known as the Battle of the Cornflakes ended, the foothills communities claimed victory.

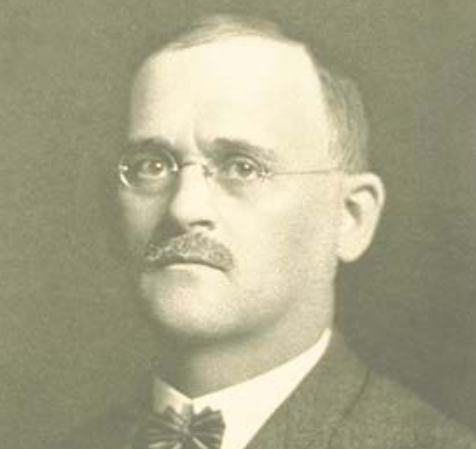

In the late 19th century, the parents of John Harvey and W.K. Kellogg raised their sons to be strict adherents to the Seventh Day Adventist religion in Battle Creek, Mich., – one that preached biologic living that encouraged good health through vegetarianism while eschewing stimulants and condiments.

Yet, as president of a local Adventist sanitarium, John Kellogg found himself dealing with patients grumbling about the healthy but admittedly boring fare served there. To remedy the situation, John, his wife and brother W.K. embarked on a series of experiments to make their healthy diet more palatable – and perhaps even attractive to their patients.

Birth of the cornflake

One night while experimenting with a more easily digestible form of bread, they left a sheet of wheat dough exposed to the air for too long. When they tried to salvage it by running it through rollers, they found it produced tasty flakes rather than dough.

After more experiments, they found that corn grit produced a more flavorful flake and offered a longer shelf life. The Kellogg’s cornflake was born.

However, Kellogg’s revolutionary

flake

inspired one of the patients at the sanitarium – a real estate

developer named C.W. Post – to enter the healthy food manufacturing

arena with his own version of Kellogg’s flake. He called it Elijah’s

Manna, but later changed the name to Post Toasties. It enraged the

Kellogg brothers.

Then

a rift between the two brothers developed when the businessminded W.K.

suggested that sugar be added to the cornflake to make it more

appealing.

After

dairy farmers began pasteurizing milk, Americans began seeking a more

convenient breakfast staple than the then-popular porridges, meals and

gruels that required boiling and constant oversight. John resisted the

suggestion.

W.K. went solo The

more devout of the brothers, John subscribed to the then-popular theory

that sweet or spicy foods accelerated the libido and facilitated sin.

Less concerned with abetting sin than providing the world with a

healthy, enjoyable and convenient breakfast opportunity, W.K. went solo,

added sugar to the cornflake and formed his own company named

Kellogg’s.

W.K. went solo The

more devout of the brothers, John subscribed to the then-popular theory

that sweet or spicy foods accelerated the libido and facilitated sin.

Less concerned with abetting sin than providing the world with a

healthy, enjoyable and convenient breakfast opportunity, W.K. went solo,

added sugar to the cornflake and formed his own company named

Kellogg’s.

However,

W.K. wanted to promote his two personal goals: he was a lover of the

Arabian horse breed and a firm believer in education as the gateway to a

successful future.

In

1925, W.K. purchased a sprawling ranch on what is today known as

Kellogg Hill in Pomona to breed what became known as the Kellogg Arabian

Horses – one of which became the most popular horse in the world when

matinee idol Rudolph Valentino chose it as his mount in his final film.

In

1949, W.K. – through his charitable Kellogg’s Foundation – deeded the

property to the California State College system to become one of the

jewels in the crown of the Inland Valley’s world-renowned educational

complex: Cal Poly Pomona.