A designer’s home is the model for building with a smaller carbon footprint.

Eco-sensitive designers and builders have long used salvaged lumber or recycled fixtures. Steve Pallrand, founder and principal designer of L.A. firm Home Front Build, is pushing even further in his quest for zero net energy, drawing inspiration from smart designs of yesteryear, and our microscopic neighbors.

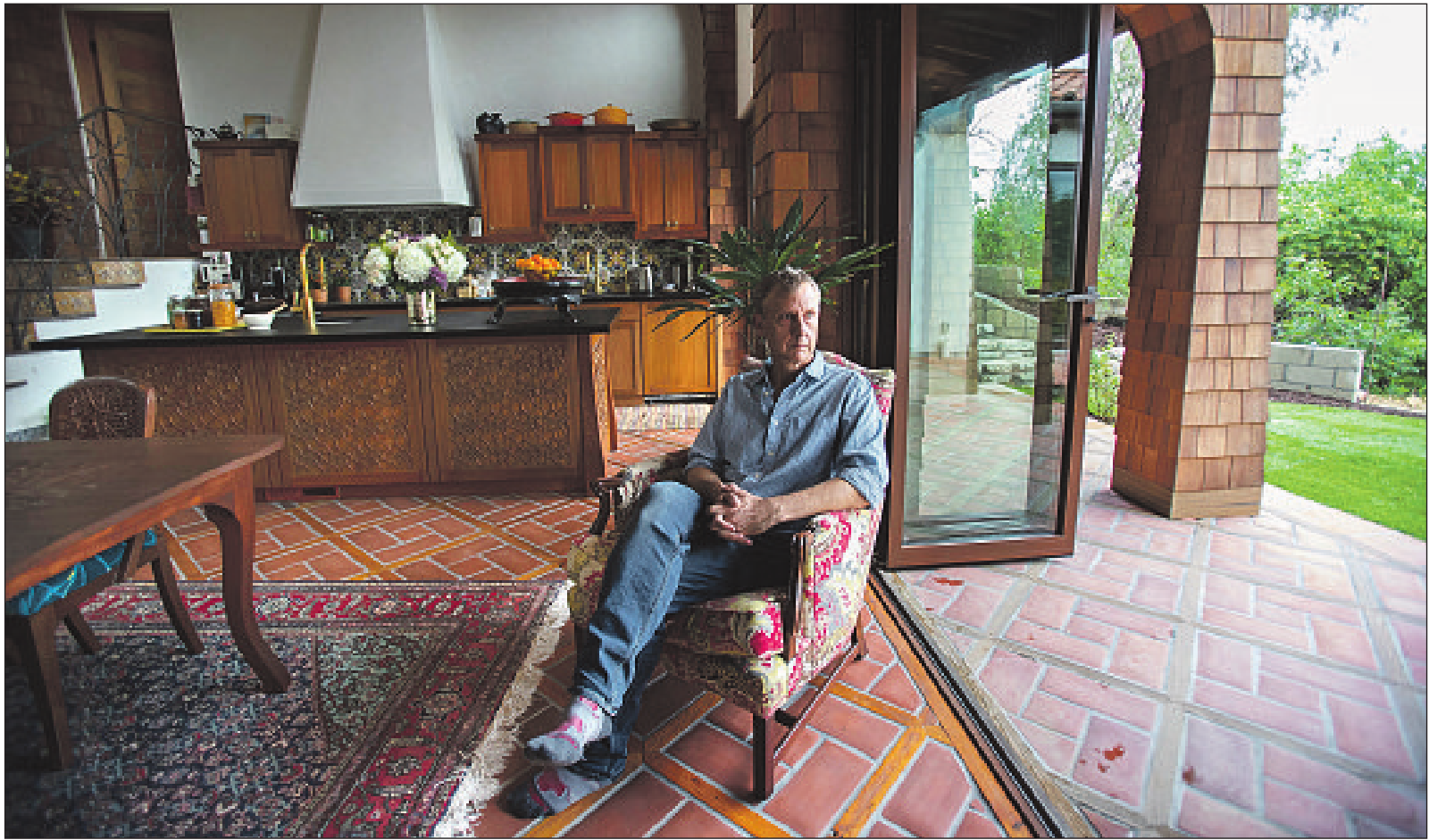

His CarbonShack initiative, to create green homes that preserve both the environment and residents’ quality of life, started with his own 2,495-square-foot Mount Washington home as the prototype.

Instead of just focusing on operational energy savers, such as solar panels or innovative heating equipment, Pallrand said he wants CarbonShack to shift its aim to “all aspects of efficiency,” and the actual way we construct our homes — “the carbon cost of the structure itself, called the embodied energy.”

Pallrand and his team turned to the design of the home itself, thick insulation, airtight windows and salvaged materials.

They even altered the composition of the concrete used in the project to make it more carbon neutral, noting on their website that concrete production alone accounts for 5% to 8% of global carbon dioxide emissions.

The firm uses “beautiful, old, viable lumber, deconstructed and rebuilt within the city to reduce the carbon footprint,” said Pallrand, whose own home is made of roughly 75% salvaged material including a local Craftsman house whose timber was headed for the dump.

“We took a house apart that was built in 1915 and framed and built it into a house in 2017,” he said.

Wood cabinets were salvaged from old church pews made out of Philippine mahogany imported in the 1920s, while the kitchen uppers and master bedroom’s redwood paneling came from a decommissioned bridge in Humboldt County that Pallrand bought and demoed four years ago.

“There

are nail holes in the wood with blackness around from the oxidization

of the iron. We leave it in because it adds character to this gorgeous,

dense, tightgrain redwood,” Pallrand said.

Long

before CarbonShack, Home Front Build already used repurposed wood on

restorations or additions to historic properties. One example, a Los

Feliz Spanish Colonial remodel and addition, seamlessly connected the

new kitchen by replicating traditional finishes so accurately, the

owner’s friend thought it was an “authentic, historic gem.”

Homeowner

and client Donald Freeman said Pallrand’s remodel on his West Hollywood

Spanish Revival was “creative, elegant and sensuous,” offering

“solutions that helped reduce our impact on the environment without the

feeling we had to give anything up.”

The

architecture, design and build firm continually draws on the past —

“when being green was anecessity, not a lifestyle choice” —for

energy-efficient designs, citing on its website the thick, insulating

walls of Spanish Revival homes that kept the indoors cool, or “the

generous sun-shading eaves that were utilized in the Craftsman &

Prairie period.”

Pallrand

credits the success of CarbonShack, and Home Front Build’s many

historic restoration projects — such as the reconstruction of the Abbey

San Encino bell tower in Highland Park, destroyed in the 1994 Northridge

earthquake —to the company’s large, in-house team of architects,

designers, artisans and tradespeople.

“We

have our own people handling the foundation, stucco, plaster, cabinetry

and tile,” Pallrand said. “People who take the time to understand the

beauty, value and worth of old plaster, framing and flooring, who bring

the touch and feel of a real person to the finishes.

“People

yearn for the feeling that some person made their house,” he said. “You

know somebody’s hand made that plaster, you know that this cabinetry

was carved by a person, so that there’s this authenticity and emotional

connection to the house.”

Alfonso

Garcia, who heads the stucco and plaster department, implements a

straw-and-plaster technique learned from his grandfather in Mexico based

on old adobe traditions.

Home

Front Build’s environmental analyst Charlie Markowitz confirmed that

adding straw (agricultural waste) to plaster also acts as a carbon

sequester, lowering its overall footprint with surprisingly elegant

results.

The

CarbonShack website engages the public in the green conversation by

openly sharing sources and offering practical tools and energy-use

calculators to help people understand their carbon footprint.

And

while bacteria and fungi are usually unwelcome in homes, Pallrand

honors them in the CarbonShack house, recognizing their importance in

nature and the symbiosis among all living things on Earth.

For

example, the whimsical swirls on the stair railing scrollwork actually

represent fungi that decompose dead plants on the forest floor, while

hand-painted bathroom tiles do not display traditional Malibu designs

but rather mimic bacteria colonies that help us digest our food — all

designed by Pallrand’s wife, artist Rachel Mayeri.

“We moved the design

paradigm to the invisible, natural world,” Pallrand said. “We’re talking

about carbon and science, so instead of looking at flowers, like

acanthus leaves on the Corinthian columns, we’re looking at mold spores

and mycelium networks.”

He

believes higher-end projects have an “opportunity to model the way

forward in home efficiency and design” as they have a “higher margin to

afford deeper analysis.”

“Our

mission is to make energy efficiency more accessible for everyone, and

communicate that highly efficient houses are not cost-prohibitive,”

Pallrand said.

“What

we’re trying to do is be more sensitive, and part of that sensitivity is

to see how the design and the building is imposing onto the

environment,” he said. “That’s critical in this time of global warming —

to lower our carbon footprint.

“We’re beyond the critical stage,” Pallrand added. “We need to face this head-on and quick.”